Herod's Law

(La Ley de Herodes)

To understand Herod's Law, it is important to understand Mexican politics. In 2000, Vincente Fox became President of Mexico. This was a big deal because Fox is a member of the National Action Party (PAN), the longtime opposition of the Institutional Revolutionary Party (PRI). The PRI held power for a little over 71 years, and thoroughly despised, and corrupt enough to remain in power for so long. Although Mexico is a democracy, open criticism of the PRI was a big no-no. If this were China, filmmakers would set their films far into the past and indirectly attack the government. The people behind this film were much more brazen, going back to 1949 and placing the PRI in all its wretched excess at the center of the film. Needless to say, this film had the possibility to be very controversial. Well, it came out, made a ton of money, and even won some awards at the Ariel Awards (the Mexican Oscars). And for some odd reason, three years after its Mexican release, now that it's political power is moot, the film arrives here.

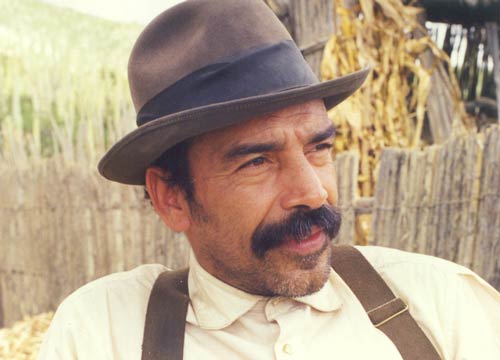

While it may be a strong political film, it's a pretty mediocre in most other aspects. Director Luis Estrada (Maten al Chacal, Amber) tells the story in broad strokes, using the typical overacting that is endemic to Mexican cinema. While this does oversimplify things, it does portray the PRI as buffoonish, which was one of his goals. The story chronicles the corruption of Juan Vargas (Damien Alcazar, El Crimen del Padre Amaro, The Blue Room), a tiny little peon in the PRI machine. His superior, Lopez (Pedro Armendariz Jr., El Crimen del Padre Amaro, Original Sin), a corrupt middle official taps him to be the mayor of San Pedro de los Saguaros, a tiny town in the middle of nowhere. Vargas jumps head first into his job, with noble ideas and intentions, and only Pek (Collateral Damage, The Mexican) to help him. He quickly realizes that the former mayor was completely corrupt, leaving no money to pave roads, rebuild the schools, or bring electricity. The primarily Indian inhabitants have a profound distrust of anything PRI, which doesn't help matters.

Almost by accident, Vargas discovers that he can extort bribes from the local brothel. He refuses first, but the fiscal crisis looms large, so what's a little money? A little becomes a little more, and soon becomes a lot. Vargas slowly succumbs to the temptations of power, and becomes what he initially hated. He tries to rationalize his actions by saying that they are for the best, and he does a great job of lying to himself. Estrada, who co-wrote the film with Vincente Lenero (El Crimen del Padre Amaro, The Blue Room), Fernando Javier Leon Rodriguez (La Tarde de un Matrimonio de Clase Media) and Jaime Sampietro (Amber, Bandidos) spare no expense in their assault on the PRI, portraying corruption and scheming at all levels, sometimes in a very sarcastic manner. As a piece of propaganda, Herod's Law is effective, however as a movie, it is a little too simplistic and has an overly familiar story. In essence, this is about Vargas and his headlong descent into ruination. Without its context, Herod's Law just becomes the same film as any number of other movies, just with a different language.